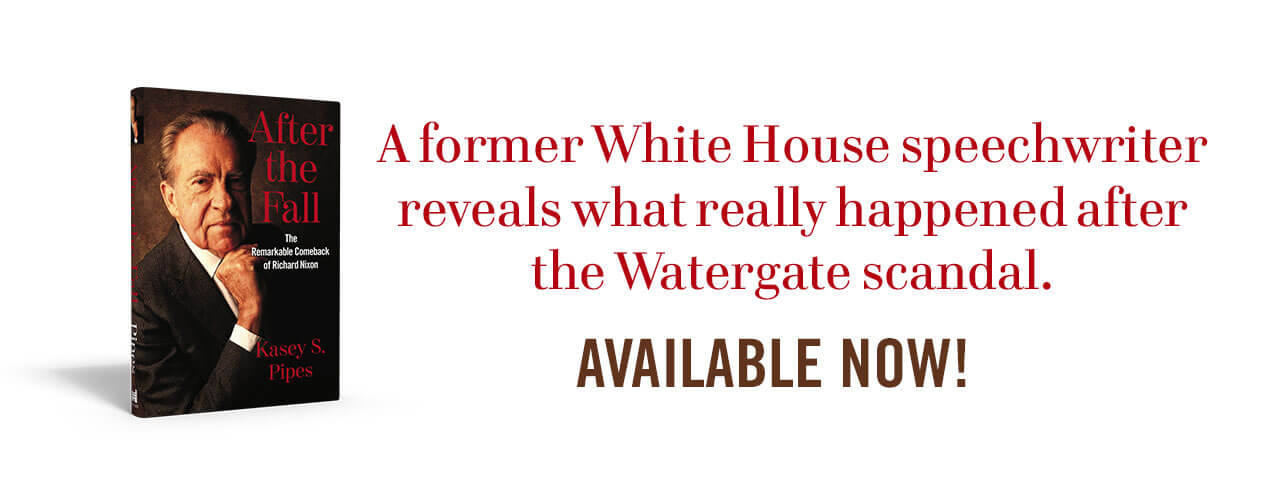

ATF OP-ED IN TOWNHALL

45 Years Later: Nixon’s Resignation Was His New Beginning

When he spoke to his staff in the East Room of the White House 45 years ago today, Richard Nixon did more than speak for the last time as president. He urged his staff—and the watching nation—to remember that “only those who have been in the deepest valley” can ever appreciate “how magnificent it is to be on the highest mountain.” He could not have known it at the time, but those would become some of the most prophetic words he ever spoke as he began his exile from public life.

This August represents the 45th anniversary of Nixon’s resignation and the beginning of his exile. Until now, much of his life after leaving the White House has been hidden. His post-presidential papers have been privately held by the Nixon family since his death in 1994. In writing my new book about this period, After the Fall: The Remarkable Comeback of Richard Nixon, I was able to secure access to these files. What I found is that Nixon may have lost formal power, but he never lost the power to influence foreign policy. Indeed, his achievements as an informal adviser to three presidents were nothing short of extraordinary.

Almost from the outset of his post-presidency, Nixon saw the way forward as one where he would be, as he wrote in his diary in late 1974, “writing a book—maybe one, maybe more—and follow it with speeches, television where possible, which will maybe put things in perspective.” This proved to be the roadmap he pursued over the next 20 years. His books on foreign policy became bestsellers; and his television appearances drew huge audiences. Forty-five million viewed the first episode of the Frost interviews–to this day the most-watched political interview in history. These forays back into the public square helped him gain private audiences with three presidents—Reagan, Bush and Clinton—who came to rely on his foreign policy advice.

CARTOONS | Tom Stiglich

View Cartoon

How valuable was Nixon as an informal advisor to the presidents? When Mikhail Gorbachev threatened to stop negotiation until and unless Ronald Reagan abandoned his plan for the Strategic Defense Initiative to protect America from nuclear attack, Nixon suggested a way out.

“I feel very strongly,” he wrote to Reagan’s national security advisor Bud McFarlane, “that the president could pull a real coup by formally offering at a summit meeting to mutually share with the Soviet Union the results of our research in our defensive outer space programs.” Nixon went on to add that such an offer would strengthen Reagan’s hand because it would “undercut” the Soviet fear that the U.S. would use the shield in an offensive way. Reagan took Nixon’s advice and made this very offer to Gorbachev. It played a vital role in helping bring the negotiations to a successful conclusion with the INF Treaty in 1987.

Years later, Nixon also found ways to use his expertise on China to help serve his country. After the Tiananmen Square disaster, Nixon traveled to China and met with Deng Xiaoping. The man who had opened the door to China in 1972 bluntly warned the Chinese leader that the same door could close again if he didn’t knock it off. One more incident like Tiananmen, Nixon cautioned, and it would be the “death” of the U.S. relationship with China. China got the message and avoided any other public displays of violence against protestors.

And shortly before his death, Nixon advised President Clinton on his dealings with Boris Yeltsin. With Yeltsin feuding with his own parliament, Nixon urged Clinton to publicly back him. He told the young president that it was “a risk to support Yeltsin, but if he goes down without U.S. support, it will be far worse.”

In fact, Clinton became so enamored with Nixon’s intelligence and advice that he traveled to Yorba Linda, Nixon’s hometown, to deliver the final word on the 37th president. In his magisterial eulogy of Nixon in April 1994, Clinton asked that “the day of judging President Nixon on anything less than his entire life and career come to a close.”

It was an amazing coda to an astonishing comeback, one that might have even surprised Nixon in November 1974, when he looked to the future and could only hope he would one day again be on the mountaintop.