NEW YORK LAW JOURNAL REVIEW OF ATF

Richard Nixon’s Climb to Redemption in the Two Decades After Watergate | New York Law Journal

It is a poignant story of a person with many flaws who quickly rose to power, was left for dead politically, rose up to reach the pinnacle of success, losing it all and now seeking to fight his way back into the good graces of his fellow citizens.

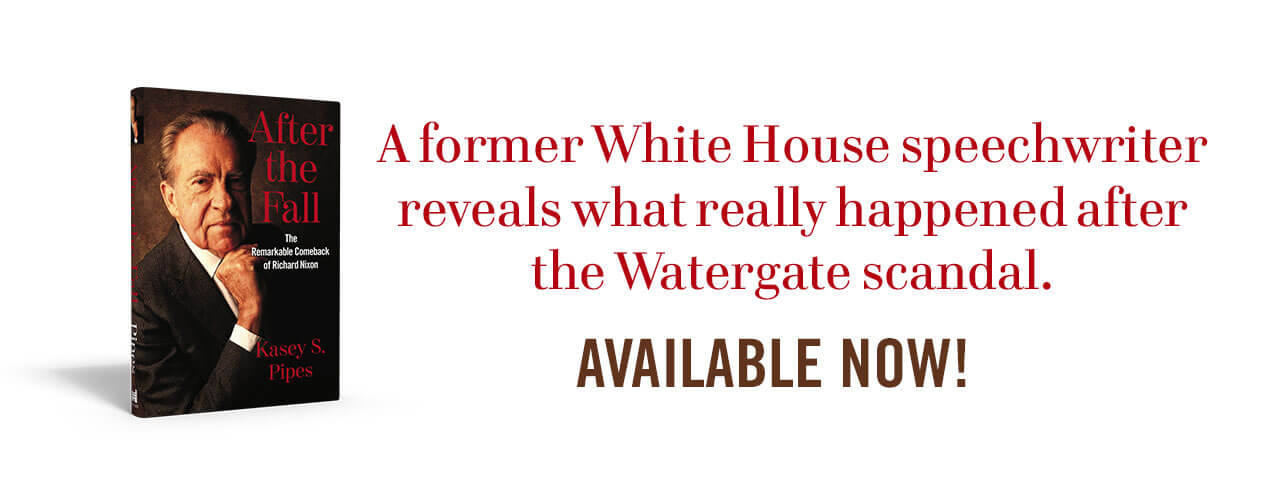

After The Fall, The Remarkable Comeback of Richard Nixon

By Kasey S. Pipes [Regnery History, 2019, 290 pages]

My introduction to presidential politics began in 1960, at age 11, with the campaign between then-Senator John F. Kennedy and the incumbent vice president, Richard M. Nixon. After eight years of the sedate Eisenhower presidency, which Ike won in two successive landslides, the country was ready for a change, or as JFK emphasized, it was time to pass the torch to a new generation. The campaign between JFK and RMN got me hooked on politics with the charismatic Kennedy versus the intellectual, but socially awkward, Nixon.

Watching on TV [yes, black and white] the crowds that turned out at rallies for each candidate were in the thousands [sorry Trump], the first televised presidential debate [which commentators said JFK won if you watched it, but that Nixon carried the day if you just listened to the content on radio] and the eventual hairsbreadth election of JFK in the wee hours of the morning after Election Day. It was one of the closest elections in history and many believed that the Democratic machine in Chicago stole it on behalf of Kennedy. Rather than challenge the results, Nixon accepted his loss and began to look to the future. In 1962, Nixon sought the governorship against incumbent Pat Brown and again came up short. The next day he held his “last press conference” so that the press would no longer have Richard Nixon to “kick around” anymore.

Fast forward to 1968. I’m now a sophomore in college majoring in political science, with an emphasis on the US presidency. 1968 was a watershed year for this country: the war in Viet Nam continued to escalate; rioting and protests against President Johnson intensified; Johnson stunned the nation by removing himself from consideration for another term as president; the horrific assassination of Martin Luther King followed just a few months later with the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, as he was on the verge of becoming the Democratic standard-bearer for the upcoming election and the eventual selection of Vice President Hubert Humphrey, amidst clashes between protesters and the Chicago police at the convention. The Republicans, seeking a conservative, law and order candidate, once again, turned to former Vice President Richard Nixon. In a race that became almost too close to call by Election Day, it was Nixon, this time, who won in another squeaker in what is regarded as the greatest political comeback in U.S. history.

Nixon’s presidency started off with great potential. He was a good president on the domestic front [creating, for example, the Endangered Species Act, which the current administration is now seeking to dilute] and an outstanding one with respect to foreign affairs [most notably his visit to China and meeting with chairman Mao and the first-ever visit by a US president to the former Soviet Union]. But if not for Watergate and his ultimate resignation, Nixon would have been viewed as one of this country’s great or near-great presidents.

Having read numerous books on Nixon that focus on his presidency, Mr. Pipes’ book covers the twenty-year period of Nixon’s post-presidency from 1974 to his death in 1994. It is a fascinating, quick read based on his access to the private post-presidential documents in the Nixon Library containing information never before reported on and gives interesting insight into Nixon’s thought processes over the years.

As the author points out in his forward, Nixon “wanted to redeem himself and be able once again, to use his greatest gift–his mind. He envisioned not a rehabilitation of his career, but a redefining of his life. He not only wanted to be accepted again, but he also wanted to shape foreign policy for years to come.” The ensuing pages focus on Nixon’s slow but steady rise into the decision-making process in foreign affairs both on a personal level and as a key adviser (often behind the scenes) for his successors in the oval office. It is a poignant story of a person with many flaws who quickly rose to power, was left for dead politically, rose up to reach the pinnacle of success, losing it all and now seeking to fight his way back into the good graces of his fellow citizens.

Following his exile from national office, Nixon moved back to his home in San Clemente to plan for the future. Several years later he moved to New York City to be closer to his daughters and their families and ultimately settled in a house in Saddle River, New Jersey, for the remainder of his life.

President Ford, in an effort to heal the nation, had been negotiating a pardon but Nixon refused to outright concede that he had committed any crimes or make any apology. The closest Nixon came to contrition was his statement “That the way I tried to deal with Watergate was the wrong way is a burden I shall bear for every day of the life that is left to me.” On Sept. 8, 1974, President Ford granted Nixon a “full, free and absolute pardon.”

Nixon had not been well since leaving office and his health had been deteriorating. Despite the multiple pleadings of his doctors, Nixon refused to go to the hospital. For years, Nixon was known to have phlebitis and now he was having acute flare-ups and there was concern that a blood clot could break loose and ultimately cause a fatal embolism. His son-in-law described Nixon as “very depressed.” By the end of October 1974, Nixon’s condition had become critical and he ended up having surgery at 5:30 a.m. on Oct. 30. Although he survived what the author refers to as his “near-death experience” he was now into heavy financial debt and his doctor described him as “a deeply discouraged man.”

Three years later, in an effort to make some much-needed money and get back in the public’s eye, the former president agreed to do an interview with TV journalist David Frost. After several interviews taped at San Clemente and subsequent editing, the program aired on May 4, 1977. It was “the most-watched news broadcast ever up to that time.” Much to everyone’s disappointment, Nixon, again, refused to admit that he committed any crimes. He allowed that “[Watergate] snowballed and it was my fault;” that he would “not get down and grovel…because I don’t believe I should.” Finally, he stated that “whether he was impeached or not was not important because ‘I have impeached myself,’” explaining that he impeached himself “by resigning.”

As the years progressed, Nixon began writing like there was no tomorrow, completing his tenth book before his death. His reflections and recommendations on foreign affairs carried great weight over the years.

A very moving vignette in the book speaks of the relationship between two former rivals for the presidency. Nixon narrowly defeated Humphrey in 1968 and his empathy for Humphrey was mentioned in a letter Nixon wrote: “Pat and I know the heartache you and Muriel must be going through to have come so close, then lost the biggest prize.” Four years later when Humphrey failed to secure his party’s nomination for a re-match, Nixon again wrote to console him: “As friendly opponents in the political arena, I hope that we can both serve our parties in a way that will serve the nation.”

Unlike today’s political parties and their leaders, who refuse to work together for the betterment of our country, there was never any rancor between past presidential candidates as currently exists. As the author wryly states, “Nixon has always liked Humphrey; Humphrey had always respected Nixon.” At the end of 1977, Humphrey was dying of cancer. On Christmas Day he called Nixon and informed him that he only had a few days to live and insisted that Nixon be present at his service in the Capitol rotunda.

Nixon was touched by this “extraordinary act of grace.” On January 16, 1978, Nixon, along with President Carter and former President Ford, attended the service. This was Nixon’s first visit back to the Capitol and to be seen in a public place of honor as an elder statesman thanks to his former political rival. Another example of Nixon’s rise in status as an elder statesman came about when President Reagan requested that he, Carter and Ford represent the United States at the funeral of Anwar Sadat in October 1973 following his assassination.

The author engages the reader in many stories of Nixon’s interactions with Presidents Carter, Reagan, G.H.W. Bush and Clinton.

Nixon developed a line of communication with President Reagan both before and after his election making many suggestions for cabinet posts and issues of foreign policy that Reagan appreciated and followed. His relationship with the White House was improving. It cooled somewhat during the Bush administration. Ironically, it reached its high point with his relationship with Bill Clinton. Clinton truly appreciated Nixon’s keen mind and understanding of foreign policy.

Although Nixon was never one to show his emotions or demonstrate public displays of affection, his love and commitment to his family, especially toward his wife Pat, ran deep. When she died on June 22, 1993, after a long battle with cancer, it was only one day after their fifty-third wedding anniversary. At her funeral, the ever-stoic Nixon let his guard down and “cried openly” before the world. Her death took a major toll on him and within a year, he, too, was gone at age 81.

The final eulogy at his funeral, at Nixon’s request, came from President Clinton, a Democrat, who thirty years earlier protested against the Viet Nam war and the man in the Oval Office, Richard M. Nixon. A baby boomer, who started in politics completely hostile to everything Nixon stood for was now standing over his casket heaping praise for the man. Among other things, he “declared himself amazed at Nixon’s mind.” He urged the country not to focus only on Watergate but to remember the totality of his life. The author referred to this as “the greatest honor” bestowed upon the late president.

The amazing transformation of Richard M. Nixon was now complete and even historians, who spent decades criticizing him, were now in awe of how he managed to become one of the country’s most respected elder statesman. The author concludes his book by quoting historian Stephan Ambrose, a major vilifier of Nixon over the course of his career: “He didn’t just survive in those last years, he thrived. He became important again. He became acceptable again. He almost became indispensable. Just incredible.”

I have often stated that President Nixon has been, and will remain during my lifetime, one of the most fascinating politicians to become president. His sheer brilliance, grit and determination enabled him to achieve so much from humble beginnings to end up suffering the ultimate indignity of being the sole president to resign from office.

His legacy incorporates his insecurities, paranoia and his inability to let go of his first defeat in 1960. Pipes describes how Nixon was always in awe of other American politicians such as Kennedy, Reagan and John Connally for their charisma, ease at public speaking and the adoration they received from others. The whole irony of Nixon’s Watergate downfall was that in 1972 he was re-elected in the greatest political landslide in presidential history up to that time. Richard M. Nixon was truly an enigma. Pipes’ book is a must-read for anyone captivated by Nixon’s carefully choreographed and steady climb to redemption in the two decades beyond Watergate.

George M. Heymann is a retired New York City Housing Court judge, an adjunct professor of law at the Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University and mediator and of counsel to Finz & Finz.